Fertility & Infertility

What is infertility?

According to the World Health Organization, infertility is “a disease of the reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse”, 15% of childbearing-aged couples globally.

As the survey carried out by Young Women’s Christian Association in 2002 indicates that infertility is rising in Hong Kong, nearly one in six couples is infertile, compared to one in ten two decades ago.

What challenges are faced by individual/couple with infertility issues?

From discovering infertility, the individual/couple will experience shock, disbelief and doubt towards the diagnosis, resulted in an urge to seek a second medical opinion, and questioned the accuracy of diagnosis. The individual/couple will also be facing decisions related to pursuing medical treatment and alternative parenting options.

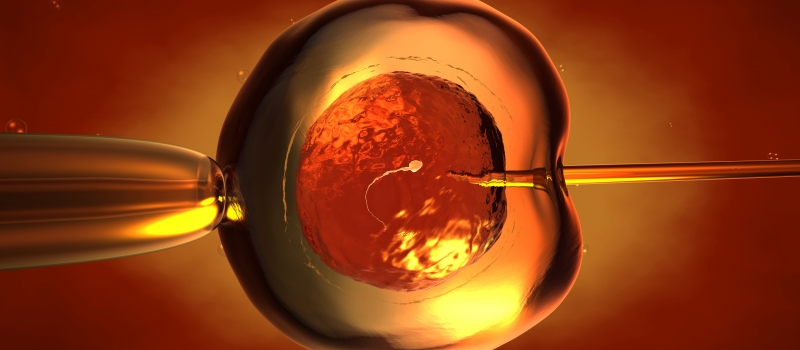

With the advancement of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ARTs), the infertile couple would have opportunity to regain their loss due to infertility. Currently, in vitro fertilization (IVF), more commonly known as “test tube baby” procedure, is the most popular form of ARTs for infertile couple. In 2010, a total of 4,016 IVF treatment cycles were conducted among 3,340 patients (Council on Human Reproductive Technology in Hong Kong, 2010).

Nonetheless, the complexity of treatment procedures, coupled by high expectation over the treatment results, will produces adverse psychological symptoms such as increased anxiety, especially when treated subjects go through an awaiting period after transferring embryo to find out if the treatment had worked (Hammarberg, Astbury & H.W.G, 2001).

In addition, high level of ambivalence can be experienced when patients need to decide whether to continue or terminate treatment when the current cycle fails, which is often embedded in a midst of socio-cultural considerations such as childbearing desire and cultural attitudes towards fertility, especially in societies who regard maternity as a central milestone in adult development and childlessness will cause major disruption in women’s lives by inferring with the established and desired life course.

All in all, infertility and its treatments poses challenges to the individual’s life tasks: self, love/sexual, community, work, couple relationship and other health concerns, which can potentially lead to mental health issues (e.g. depression and anxiety), lowered self-esteem and self-worth, and dampened quality of life in the long run.

How to live with infertility?

Developed by a local team of social workers, the IBMS intervention aims at enhancing the holistic well-being of Chinese infertile women. It is believed that the IBMS intervention is more comprehensive and culturally relevant compared to other psychosocial interventions.

The IBMS shares some similarities with existing mind-body therapies as they both include relaxation skills training such as meditation, guided imagery, and mindfulness training (Chan et al, 2011). While few interventions have component that deals with people’s spiritual well-being, the IBMS aims at promoting spiritual well-being by fostering resilience and spiritual transformation. Since other studies Domar et al (2001) had proved that the levels of spiritual well-being were negatively correlated with distress and depressive symptoms related to infertility, it is believed that the IBMS is of great importance to alleviate symptoms and achieve the general well-being from physical, psychosocial and spiritual perspectives.

What are the findings from I-BMS project?

The effectiveness of I-BMS intervention on anxiety reduction for women undergoing in-vitro fertilization (IVF) has been proved by randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Chan et al (2006) found that women who participated in the I-BMS alleviated the situational anxiety for IVF treatment and further improved their holistic well-being. In the current study, the I-BMS intervention is also anticipated to be helpful as a self-administered package for individual women in need. Adopting a randomized controlled trial design, the study will provide evidence on whether and how this self-administered intervention may help individuals who are at awaiting period of IVF results.

More recently, the I-BMS team condenses the intervention elements into a self-help package for women undergoing IVF treatments in order to enhance their psychological adjustment and coping during the 14-day treatment result-waiting period.

The self-help kit contains information about the relationship between stress and infertility, body-mind exercises, therapeutic massaging, meditation and breathing exercises. Participants will attend a workshop before their IVF treatment and be delivered the self-help package afterwards. Pilot study with 42 women showed the self-help kit helped decreased the anxiety level, as compared to those who received no psychosocial intervention.